Python's data science ecosystem matures – the case of Polars

It simply feels amazing to finally get something you were waiting for, after many years. This is a story about Python, data science, and software library design. The star: Polars.

Welcome to the first post on my blog! 👋 This one is very technical, but I want to cover very diverse topics in the future. Let’s see how it goes.

Frustrations with Pandas

If you are familiar with data science and Python, then you surely have used the Pandas library. It’s a de-facto standard tool for manipulating data frames – tables of data with columns and rows. It has a simple, easy-to-learn API and is well-integrated with the rest of the Python ecosystem. It was also a source of my many frustrations since I started using it, making it one of my most dreaded and, at the same time, most used tools.

Pandas is great, but over time, I started noticing more and more of its limitations. One of the most obvious ones is the inconsistent and confusing API. I could never properly memorize in which contexts the square braces ([]) were for selecting columns or rows, or when does a method return a view (and can this view be modified) over a DataFrame or its copy. Filters are janky. The groupby method has a few different styles of argument specification that I always have to look up – same with apply and a few others. Indexes (especially multi-level indexes) are confusing to use and don’t seem to be useful in most cases. The list goes on – in general, the API looks like it evolved organically over time, without a specific design philosophy. For me, this makes Pandas harder to use, which slows down work and wastes time.

The second big frustration I had was with handling larger-than-memory datasets. Pandas always loads everything into memory, making it plain impossible to work on some relatively common workloads, like processing a large dump of sensor data from experiments. This can be alleviated by pre-processing the data using something simpler (like the GNU command-line tools that come with Linux), or rolling out the big guns – something like Dask. Instead of using eager evaluation (like Pandas), Dask builds a computation graph (i.e., query plan) that is then lazily evaluated. It can work with data residing in files, has a built-in optimizer, and can even distribute workloads across multiple machines. The issues I had with it was that it had a limited feature set, still inherited the other downsides of Pandas, and added its own layer of complexity. It does work, but for me it’s just wonky.

Finally, Pandas is just slow. In more complex scenarios, you may need to introduce some Python code to handle a more complicated task, which will instantly reduce the performance dramatically. Even if you avoid this and try the many interesting performance tricks, the processing speed for me always left something to be desired. Dask doesn’t help this much, especially for workloads that are inherently single-threaded.

The broader context

These are not new issues, they are well-known to the community, and many solutions for them were proposed, of varying usefulness.

I was often left wondering if I could just use the R language and then all my problems would go away. I was always under the impression that the R data table system was much more consistent and thought-through – same goes for the excellent ggplot2 library versus the incredibly messy matplotlib in Python.

Although R is a near-perfect ecosystem for data science, it lacks one thing that for me made it impossible to make the switch: the vast collection of libraries written in Python. If I worked only with data science and machine learning, it would be fine – but what about libraries for knowledge graphs, HTTP servers, MediaWiki parsers, MQTT connectors, computer vision, SSH remoting, connecting to weather stations over serial, processing architectural models (BIM), and many, many more?1 I’m sure you can do all of this somehow in R… but I think we can all agree that Python does have an outstanding ecosystem of libraries for basically everything. This alone makes it worth sticking with, at least for me.

What we needed all this time: Polars

Recently I’ve stumbled upon the (relatively) new Polars library, and it turned out to be everything I needed all this time. It is incredibly fast, by the virtue of smart vectorization, using columnar storage (same idea as DuckDB – another hot topic), and being written in Rust. It has a consistent and well-designed API that actually makes sense. It supports not only lazy evaluation with a query optimizer, but also (experimentally) streaming evaluation. Stream processing is especially interesting, because it could allow for supporting datasets of arbitrary size, even on a single machine. I will come back to the topic of stream processing in a future post.

So far I have used Polars in a few data science notebooks, and the results were very good. I had no trouble learning the new syntax and the performance is just as advertised – blazing-fast. I will certainly replace Pandas with Polars in all my future data science projects.

The one thing that Polars does not implement is distributed computing, which is offered by Dask. For me, this is not an issue (more of an advantage, really, due to lower complexity), as I do not work with data that would require distributing the workload. Most of the time I’ve found you can squeeze out a lot of performance by efficiently using the resources of a single node (multithreading, vectorization). With modern CPUs that can crunch vectors with impressive throughput, a lot more can be done on a single node, if you can use this potential. Polars can.

The future

Pandas is a great tool, don’t get me wrong. I very highly respect the incredible amount of work put into it by its developers. But, I see it as a step in the evolution of the data science ecosystem, which must move forward to stay relevant. Sometimes, it is better to drop a set of assumptions that don’t work so well anymore, start from scratch, and build something drastically better. I hope that Polars will be this thing.

I think the long-term success of Polars will depend on its integration with the wider Python ecosystem. What I really, really, really want to see is an implementation of the Seaborn statistical plotting library over Polars, with a completely redesigned API, akin to R’s ggplot. There is in fact some progress in this direction with Seaborn experimenting with a completely new API for plotting, and there being already some rudimentary support for plotting from Polars DataFrames. The latter is unfortunately realized by making a full copy of the data to a Pandas DataFrame… so we are not getting any of the performance advantages. I hope the developers of Seaborn will see this opportunity and catch on to it. Then, Python data science will be truly unbeatable. 💪

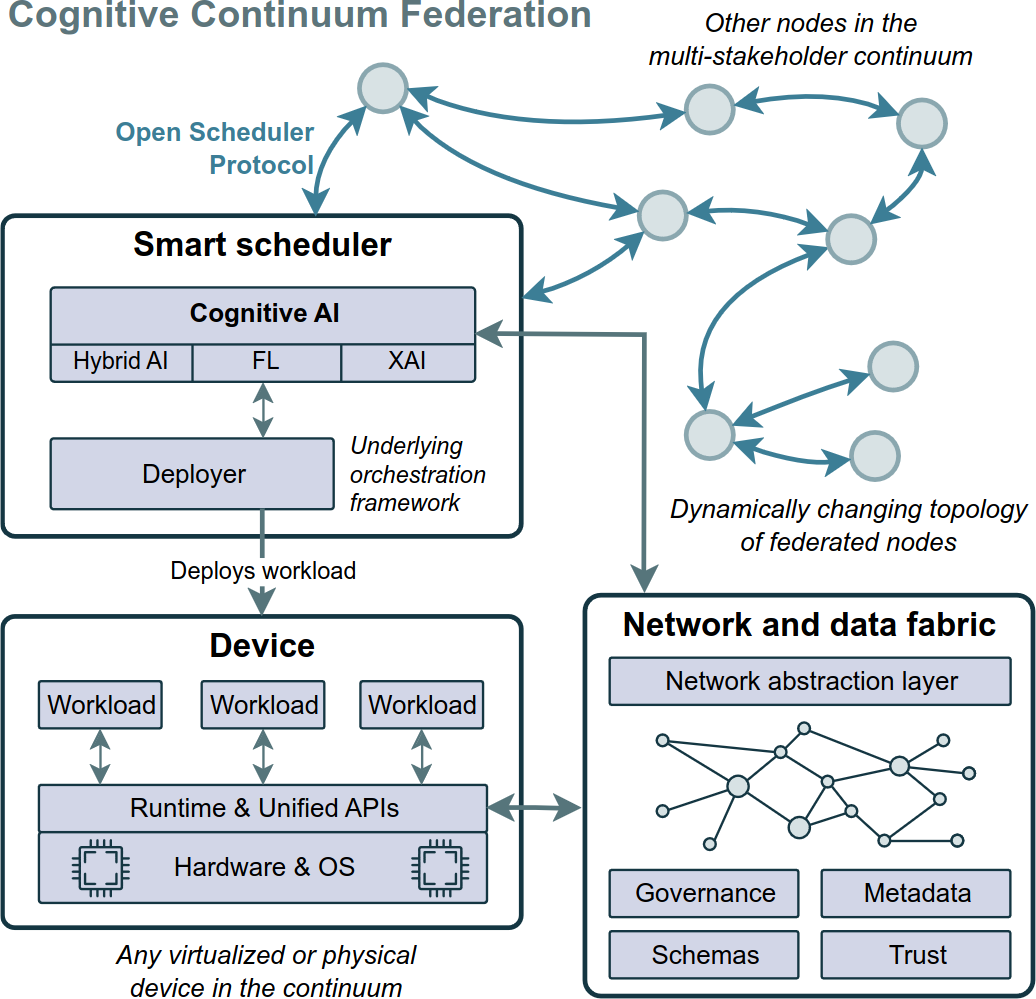

Polars also has an equivalent API in Rust, so it may be possible to introduce support for more languages in the future. I’m especially curious if one compile it to WebAssembly and use as a basis for future data-crunching Cloud-Edge-IoT applications (Sowiński et al., 2023). But this is a rather distant future. Or is it? 🤔

Footnotes

-

Yes, I did use each of these libraries at some point. ↩

References

- IEEE CloudNet 2023

Autonomous Choreography of WebAssembly Workloads in the Federated Cloud-Edge-IoT ContinuumIn 2023 IEEE 12th International Conference on Cloud Networking (CloudNet), 2023

Autonomous Choreography of WebAssembly Workloads in the Federated Cloud-Edge-IoT ContinuumIn 2023 IEEE 12th International Conference on Cloud Networking (CloudNet), 2023